by Mannahattamamma (UAE) | Dec 10, 2014 | Expat Life, Feminism, Gun Violence, News, Prejudice, Social Media, Tragedy, UAE, USA

“Are you okay?” The emails and Facebook queries began pouring in even before I knew what had happened. “Were you there?” One particularly dramatic friend asked if “what happened” made me think about moving home.

“Are you okay?” The emails and Facebook queries began pouring in even before I knew what had happened. “Were you there?” One particularly dramatic friend asked if “what happened” made me think about moving home.

Their queries followed the terrible news that had gone viral almost as soon as it happened: in a mall bathroom in Abu Dhabi, where I live, a veiled woman had killed a Western woman—-an American teacher-—with a long kitchen knife. Adding to the horror of the attack was the fact that the victim’s children, eleven-year old twins, were apparently hanging out in the mall waiting for their mother to come back from the bathroom.

I didn’t hear the news until I got home from work that day and opened Facebook. I suppose that people were particularly worried because I am also an American teacher, and about a month ago, the US Embassy in Abu Dhabi reported that anonymous threats against American teachers had been made on a jihadi website. For a day or two after the attack, news reports tossed around the possibility that the veiled woman was somehow in league with ISIL, or some other terrorist organization.

As it happens, however, the murderer had no discernible terrorist allegiances, and what happened in that mall bathroom was just an appalling act of violence. Some of us who live here speculated about the difference between what happens in the US when an unstable person finds a weapon and what happened here:

a butcher knife is a brutal instrument, it’s true, but it creates far less mayhem than, say, a semi-automatic rifle.

According to a 2007 survey, the US ranks first in the list of number of guns owned by civilians (90 guns per 100 residents); the UAE ranks 24th (22 guns per 100).

Violent crime is incredibly rare in Abu Dhabi. Yet, despite the rarity of violence here, and despite the stability of the Gulf States, there was the chatter on Facebook; there were the emails; there were the questions about whether this attack would cause me to move home. “Home” is a bit complicated for me: I’ve lived in Abu Dhabi for almost four years, but had been in Manhattan for almost twenty years before that. So “home” is here. . . and there.

Before we moved to Abu Dhabi, my family and friends were worried about other things. “Are you going to have to, you know,” they’d ask, swirling their hands around their head as if describing the world’s biggest beehive hairdo. Their swirl implied “covering”: would I have to wear a headscarf or an abaya when I went out in public? The answer is no. I feel free to walk around alone wherever I please, dressed much the same way I would be in New York. There are no laws governing how people dress here; women are free to cover or not cover, and on the beaches you see burqas and bikinis with equal frequency.

In fact, I feel as safe walking alone in Abu Dhabi as I ever did in New York. It’s the kind of place where I leave the car doors unlocked when I run into the grocery store, and where more than once I’ve forgotten my phone in some public place, only to run back ten minutes later to find it exactly where I left it.

I share the sentiments of my local friend, Ken. In response to the news, he posted the following message on his Facebook page: “Thank you for your e-mails and messages about the American woman who was killed here on December 1st. I appreciate your concern. But please be assured that I don’t feel in any greater danger being a Westerner in Abu Dhabi than I felt being a gay man in New York City. In fact, it’s the opposite. I’m used to danger.

The only way to protect oneself completely from acts of terror or random violence is by not participating in the world. I won’t do that.”

The expressions of worry that came from my family and friends in the aftermath of this attack were real, I know. And there is no doubt that what happened is appalling and has ripped apart the lives of this woman’s family. But I can’t help but suspect that this story got as much coverage as it did (there are more than thirteen pages of hits for “American teacher slain Abu Dhabi) because the attacker is so visibly Other: a veiled woman, an exotic symbol of “the Middle East,” which to much of the West is still an undifferentiated blur of veils, oil rigs, and jihadis.

Here’s the teaser from CNBC when the story about the knife attack first broke:

I wonder about the leap: that an attack in a mall bathroom by a woman with a knife might have implications for “foreigners” living anywhere in the Middle East.

It’s a strange twist, isn’t it, to think that had the Western media simply assumed that the attack was an isolated, horrifying incident—the work of one crazy woman—it might have represented a step forward?

This is an original post written for World Moms Blog by Deborah Quinn.

Photo Credit: Daily Mail

After twenty-plus years in Manhattan, Deborah Quinn and her family moved to Abu Dhabi (in the United Arab Emirates), where she spends a great deal of time driving her sons back and forth to soccer practice. She writes about travel, politics, feminism, education, and the absurdities of living in a place where temperatures regularly go above 110F.

Deborah can also be found on her blog, Mannahattamamma.

More Posts

Follow Me:

by Shaula Bellour (Indonesia) | Dec 4, 2014 | 2014, Awareness, Being Thankful, Cultural Differences, Domesticity, Expat Life, Family, Home, Husband, Indonesia, International, Kids, Life, Life Balance, Life Lesson, Living Abroad, Motherhood, Parenting, Responsibility, Shaula Bellour, Twins, World Motherhood

This month marks our third anniversary of living in Jakarta. Considering how empty our house was when we first arrived here, I am staggered at how much stuff we have acquired in that short time.

This month marks our third anniversary of living in Jakarta. Considering how empty our house was when we first arrived here, I am staggered at how much stuff we have acquired in that short time.

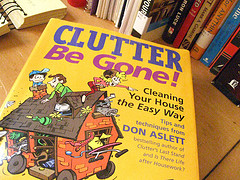

We initially started out with garden chairs as living room furniture and took our time furnishing our new space. Though the house isn’t exactly cluttered, it feels full – and I feel daunted by the sheer volume of STUFF that seems to fill every closet and drawer.

It’s the never-ending tide of cheap party favors, orphaned toy and game parts, and plastic galore. It’s the piles of paper: children’s artwork, old receipts, and unfinished magazines. It’s all the things I never use or wear, the boxed objects I might use one day and the stock of (US-bought) items I think I can’t live without.

Moving from the US to East Timor 5 years ago was a great opportunity to clear things out and scale back. Although I did feel a little sad watching an expectant dad cart away our twins’ disassembled cribs the night before we moved, it felt good to sort through our accumulated belongings and assign categories: donate, sell, ship or store.

Donating unwanted items was easy. I arranged for a pick up with a local charity group, stacked everything on my porch and it was all magically whisked away. We sold our car and other big items, sent friends home with plants and other housewares and shipped our edited possessions to Dili.

Everything else went into our storage unit. A few years later I visited it for the first time and was amazed by what we’d deemed worth keeping at the time. I randomly peeked in a few boxes and found…sweaters. Lots of sweaters. What was I thinking? It was winter at the time and we didn’t know how long we’d be away, but still.

We also stored our furniture, though we recently realized that the cost of storing it for the last five years has probably exceeded its value. While visiting the US, my husband spent a day digging out furniture and giving it all away – couches, tables, lamps, washer/dryer…everything. I was thousands of miles away at the time but it felt fantastic.

Leaving East Timor prompted a similar purge. And yet here I am again, feeling the urgent need to reduce and simplify.

Here in Jakarta, this process isn’t as straightforward. While it’s fair to say that nothing will ever go unused, getting rid of unwanted items isn’t as simple as piling them on the porch. I frequently give outgrown kids’ clothes and shoes to friends or neighbors, donate household items to women’s association charity shops, or leave things out to be upcycled by our handcart-pulling bin man.

Last month my children got involved and we went through their toys, books and clothes and filled 10 bags with donations for a local orphanage. Though it was good for them to be part of this process, I would also really like for them to see where their donations are going and consider giving back in other ways (time, money, materials etc.).

Although I will never be a minimalist (or a light packer…), I’m committed to scaling back and am hopeful that this is a first step toward living with less.

A quick internet search reveals hundreds of creative ways to de-clutter, organize and simplify our homes – and ultimately our lives. We are told that having too much stuff is draining and overwhelming us, that we are wasting too much time and money managing our things and that getting rid of all this stuff can make our lives richer and happier.

All of this may be true, but for me the bigger question is about how to acquire less stuff in the first place.

Clearly I don’t have the answer yet, but it’s definitely something I would like to explore and practice – starting now.

Please share your strategies and tips to get me started!

How do you minimize/manage the “stuff” in your house and life? Do you have any tips for living with less?

This is an original post for World Moms Blog by Shaula Bellour.

Shaula Bellour grew up in Redmond, Washington. She now lives in Jakarta, Indonesia with her British husband and 9-year old boy/girl twins. She has degrees in International Relations and Gender and Development and works as a consultant for the UN and non-governmental organizations.

Shaula has lived and worked in the US, France, England, Kenya, Eritrea, Kosovo, Lebanon and Timor-Leste. She began writing for World Moms Network in 2010. She plans to eventually find her way back to the Pacific Northwest one day, but until then she’s enjoying living in the big wide world with her family.

More Posts

by Tina Marie Ernspiker | Nov 28, 2014 | 2014, Cooking, Education, Expat Life, Family, Husband, Living Abroad, Mental Health, Mental Illness, Mexico, Motherhood, Parenting, Water, World Motherhood

As a wife of one and a mom of four, it seems like I am always learning and discovering! I know I am not alone. Let’s just admit it: The world is a big place, life is a lesson, and children can be the best teachers. Normally my series, Life Lessons with Mexico Mom, is hosted on Los Gringos Locos, but today I am posting here on World Moms Blog.

As a wife of one and a mom of four, it seems like I am always learning and discovering! I know I am not alone. Let’s just admit it: The world is a big place, life is a lesson, and children can be the best teachers. Normally my series, Life Lessons with Mexico Mom, is hosted on Los Gringos Locos, but today I am posting here on World Moms Blog.

Here are my insights and experiences as a Mexico Mom for this week:

Life Lesson 25: The city of Morelia, Mexico may shut off your water at any time without given notice. If this happens make sure your water tank is full! We have to press a switch to fill our water tank every other day or so. If we forget, we are without water for a few minutes. If the city turns off the water, we may be without water for a day. Then our wonderful landlord brings us a huge barrel of water for the toilets and the dishes. Yea!

Life Lesson 26: Driving through Morelia you could very well see a naked woman in the middle of the street. Unfortunately there is not much government help for the poor and mentally ill in our city. This part is actually very sad. My husband saw this poor lady, stark naked, with a pile of clothes in front of her. Chances are she was homeless and mentally ill. Cars were slowing down and people were staring. Brad was flabbergasted. There is not much he could have done for her. She would probably have been scared of my large, white husband.

Life Lesson 27: It is not necessary to have a stove and oven. Since we moved into our new house a month ago I have been without this appliance. I miss it dearly and hope to purchase one very soon. But on the upside, we have discovered just how much you can cook on a grill. Banana bread, pancakes, casseroles, scrambled eggs, quesadillas, pulled pork, and lots more! Brad has become a professional grill chef. Cooking is not my forte, so I am loving it!

What life lesson did you learn this past week? Please share it with us below. We want to hear your thoughts from around the world!

This is an original post to World Moms Blog by Tina Marie Ernspiker. Tina can be found blogging over at Los Gringos Locos. She is also on Facebook and Twitter.

Photo credit to A. Hurst Photography

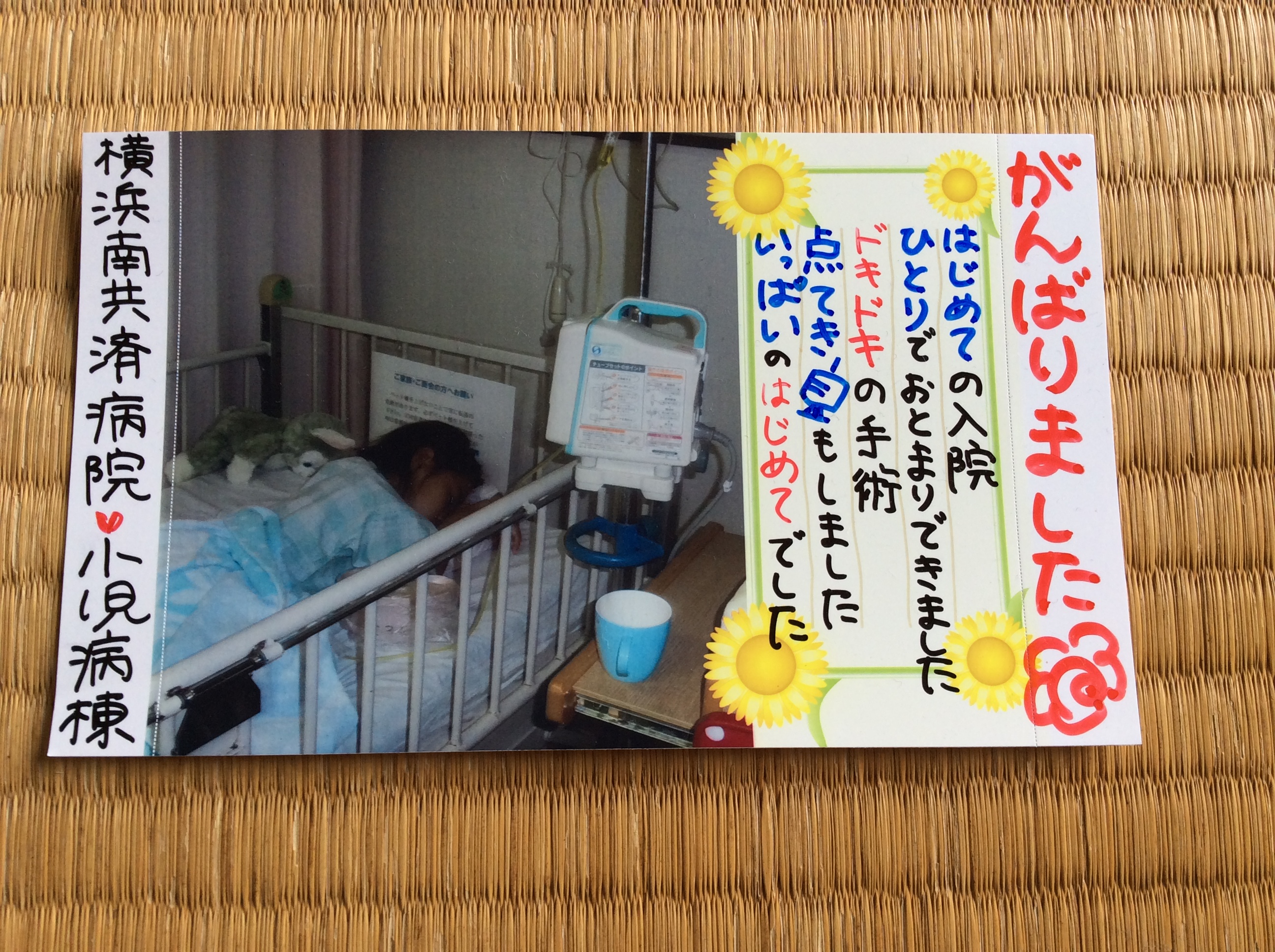

by Melanie Oda (Japan) | Oct 16, 2014 | 2014, Awareness, Being Thankful, Child Care, Childhood, Cultural Differences, Culture, Expat Life, Eye on Culture, Family, Health, Hospital, International, Japan, Kids, Life Balance, Life Lesson, Living Abroad, Milestones, Motherhood, Parenting, World Motherhood, Younger Children

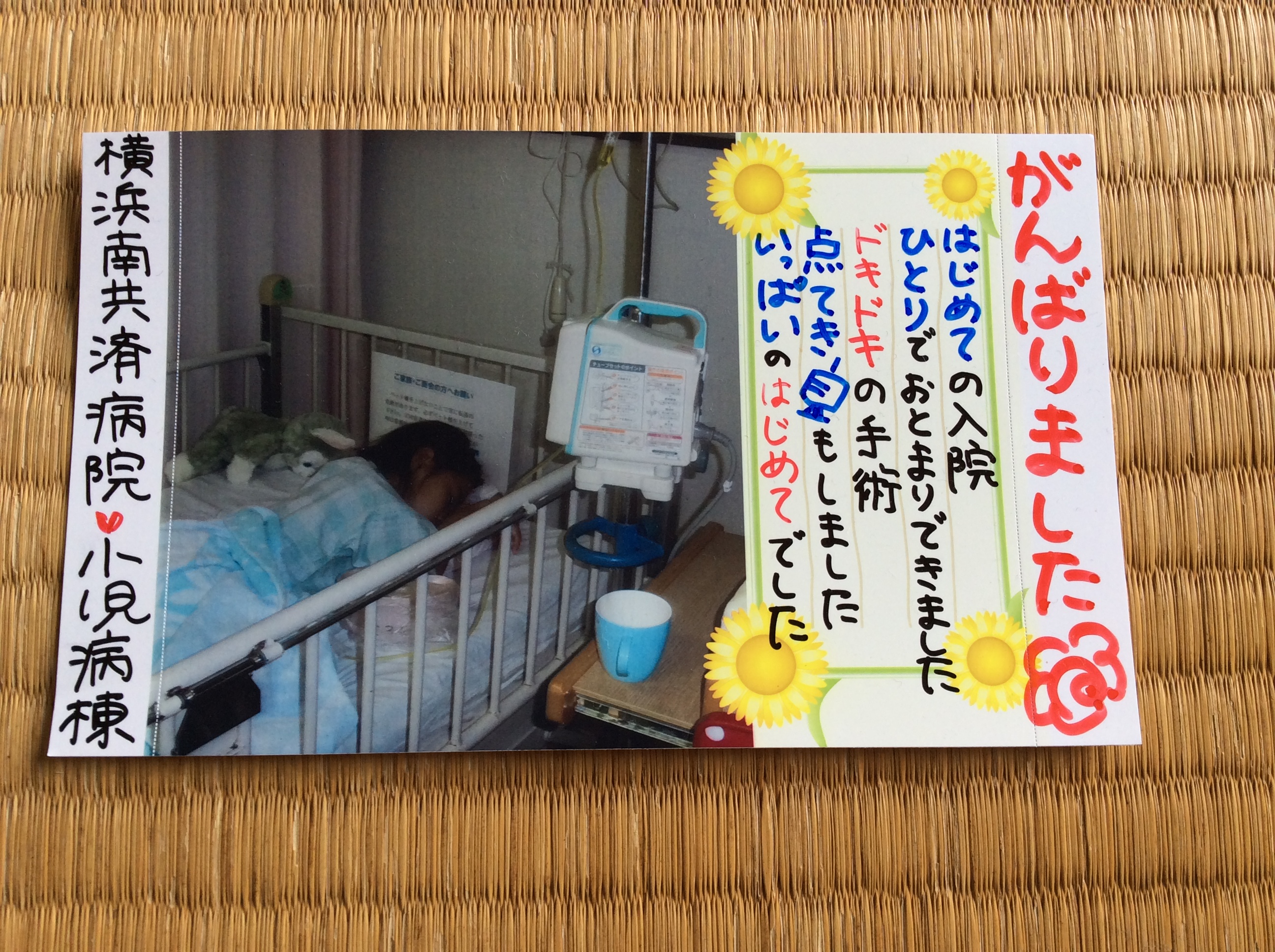

My 6 year-old daughter had her tonsils and adenoids out over summer vacation. She had been diagnosed with sleep apnea several months earlier and since nothing else was helping, finally I reluctantly agreed to the surgery.

My 6 year-old daughter had her tonsils and adenoids out over summer vacation. She had been diagnosed with sleep apnea several months earlier and since nothing else was helping, finally I reluctantly agreed to the surgery.

I was reluctant because hospital “culture” in Japan is very different from the US, where I am from, and because I knew I would be up against another cultural wall in regards to care for my older child.

This surgery, that requires a one-night stay in the hospital in either the US or UK (according to some quick research on my part,) here in Japan means seven nights in the hospital.

Since hospital rooms are shared, parents are not allowed to stay over night for any except the youngest of patients. Parents are expected to provide clean laundry and cutlery for the patient every day.

The children’s ward had a strict daily schedule, with times when they we’re confined to their beds (which literally had bars like a prison cell,) and times when, if they were well enough, they were allowed to use the playroom.

But absolutely under no circumstances whatever could they leave the children’s ward. And visitors under the age of 15 were not allowed in the ward.

This was a conundrum for me. I have a 9 year old son, who was on summer vacation at the time, and a husband who works 12 hour days, on a good day.

Hospital culture in Japan is strangely at odds with the wider culture in general. A high percentage of children co-sleep with their parents well into their elementary years. That is the cultural norm.

However, the hospital where my daughter had surgery, would not allow parents to spend the night with children over 2 years old.

This particular hospital allows parents of small children to stay until they fall asleep, but for my daughter, that may actually have been worse. Come lights out at 8pm, there was more crying in the children’s ward than from the nursery down the hall.

I had another child waiting at his friend’s house or at Baba’s (grandmother’s) house for me to come home, after all. My husband tried to get home from work at a decent hour, but I think he made it by 7pm once.

The day after the surgery, when my daughter was still feeling ill from the effects of the anesthesia and started bleeding from her nose, I was very grateful that she was in the hospital where I could have a professional attend to any concerns with the push of a nurse-call button.

Around Day 3, though, I could feel myself beginning to fall apart, fiber by fiber. The stress and plain old-fashioned exhaustion were starting to get to me.

My son at home was starting to feel the effects of being shuffled from place to place numerous times a day. My daughter wasn’t sleeping well and wanted to come home. I begged the doctor to discharge her a bit early, even a few hours would be great. His response was that the other child in the same room who’d had the same surgery on the same day was not recovering as well, and it would be upsetting for her if mine left earlier.

Excuse me, what? I thought, blinking several times, sure I had misheard. But I hadn’t.

On the day she was finally discharged, the nurses and staff presented her with a postcard, complete with a photo of her post-op, “to remember them by.” My first instinct was to burn it. Who would want to remember this? But I kept it, an ironic little reminder of the Japanese tendency to have “entrance” and “exit” ceremonies for everything.

I was reminded of a speech the principal of a junior high gave to the student body to announce that I was leaving: “People enter our lives, and at some point we must be parted. We should cherish each of these events.” Perhaps one day my daughter will value the card.

For now, she gets angry every time she sees it. The poor little girl has been waking up at night just “making sure I’m at home” for the past several weeks.

But now I look at the card and I feel profoundly thankful that my kids are, for the most part, healthy and happy. I don’t know how parents, who have to juggle (and it is a juggling with knives-type event, not harmless bean bags) a child’s hospitalization—along with the mundane tasks of everyday life that just keep coming, even when we are least able to deal with them—do it.

I say a little prayer for you every night, moms I do not know, and wish you strength and patience and space to breathe.

Has your child ever been hospitalized? What was it like for you, as a parent?

This is an original post to World Moms Blog from our mother of two in Japan, Melanie Oda.

The image used in this post is credited to the author.

If you ask Melanie Oda where she is from, she will answer "Georgia." (Unless you ask her in Japanese. Then she will say "America.") It sounds nice, and it's a one-word answer, which is what most people expect. The truth is more complex. She moved around several small towns in the south growing up. Such is life when your father is a Southern Baptist preacher of the hellfire and brimstone variety.

She came to Japan in 2000 as an assistant language teacher, and has never managed to leave. She currently resides in Yokohama, on the outskirts of Tokyo (but please don't tell anyone she described it that way! Citizens of Yokohama have a lot of pride). No one is more surprised to find her here, married to a Japanese man and with two bilingual children (aged four and seven), than herself. And possibly her mother.

You can read more about her misadventures in Asia on her blog, HamakkoMommy.

More Posts

by Shaula Bellour (Indonesia) | Sep 25, 2014 | 2014, Childhood, Expat Life, Family Travel, Holiday, Indonesia, Shaula Bellour, Twins, UK, Uncategorized, USA

From the window, I can hear high-pitched giggles and the sound of wellington boots on garden path gravel.

From the window, I can hear high-pitched giggles and the sound of wellington boots on garden path gravel.

My daughter is next door with her new neighbor friend, pretending that the garden shed is an animal rescue center and the backyard chickens are actually wild monkeys. My son is bouncing on a trampoline with the friend’s big sister and I can see their carefree bodies flying above the wheat fields, in the shadow of the village church.

It’s past their usual school-night bedtime, but the sun is still high and we’ve stopped keeping track of these things anyway. Evidence of the day’s activities is scattered on the grass: badminton birdies, a rainbow of half-finished loom band bracelets, a decorated cardboard lean-to and sticky signs of an earlier snail race.

Both kids return with dirty feet and ice cream on their faces and I’m pretty sure they forgot to wash their hands after petting the donkey across the road. But it’s okay. It’s the summer holidays in rural England and it feels like the stuff childhood is made of. The only catch is that it’s not where we live…

Life is a series of trade-offs.

Back in Jakarta, we’re on our way to school and my children want to know why we don’t live in England. “Well…because we live here”, I respond simply, feeling a sharp pang of guilt. I go on to explain that day-to-day life in England would probably be different than the idyllic summer version. For example, instead of playing all day, they would have to go to school and soon the long sunny days would turn cold and wet. “That’s okay!” they chirp, happily unconvinced.

Luckily the conversation shifts and together we watch the city float past our car window. The daily mosaic of life here is colorful, chaotic and always fascinating. We read shop signs, point out our favorite kaki lima food carts and compete to find the most interesting motorcycle cargo…from pallets of baby chicks to enormous balloon bundles.

We talk about their new school classes and where all the children are from, realizing that there are nearly as many nationalities as students. We think about where we might like to travel for their half-term break and marvel at how lucky we are to be so close to so many amazing destinations.

Life is a series of trade-offs.

Sometimes, I feel sad about the fact that our children are growing up so far away from their grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. But then I am also reminded that since our family is both British and American, we will always be far from someone we love regardless of where we live. We do the best we can to stay connected and are grateful for the precious time we get to spend together.

Occasionally, I see photos of my friends’ frolicking children and feel a twinge of regret that my own kids are missing out on the places and experiences I enjoyed as a child growing up in the US.

But then I examine my own assumptions…does their childhood need to resemble my own for it to be good? Of course not. My children may not learn to ski anytime soon, but they are seeing and doing so much more than I ever dreamed of at their age.

Life is a series of trade-offs.

I tell myself that we are lucky to enjoy the best of both worlds. But in reality, we can’t have it both ways.

This is the path we’ve chosen and there are limitations as well as benefits. Accepting these trade-offs brings a certain kind of relief and shifts the focus — emphasizing what we have instead of what we’re missing.

It’s a process, but I’m getting there.

How do you and your family balance life’s trade-offs?

This is an original post for World Moms Blog by Shaula Bellour.

Photo Credit: ClairOverThere. This image holds a Flickr Creative Commons attribution license.

Shaula Bellour grew up in Redmond, Washington. She now lives in Jakarta, Indonesia with her British husband and 9-year old boy/girl twins. She has degrees in International Relations and Gender and Development and works as a consultant for the UN and non-governmental organizations.

Shaula has lived and worked in the US, France, England, Kenya, Eritrea, Kosovo, Lebanon and Timor-Leste. She began writing for World Moms Network in 2010. She plans to eventually find her way back to the Pacific Northwest one day, but until then she’s enjoying living in the big wide world with her family.

More Posts

by ThinkSayBe | Jun 12, 2014 | 2014, Africa, Awareness, Being Thankful, Communication, Discipline, Education, Expat Life, Eye on Culture, Family, Girls, Humor, Older Children, Parenting, Technology, Teenagers, ThinkSayBe, USA, World Motherhood

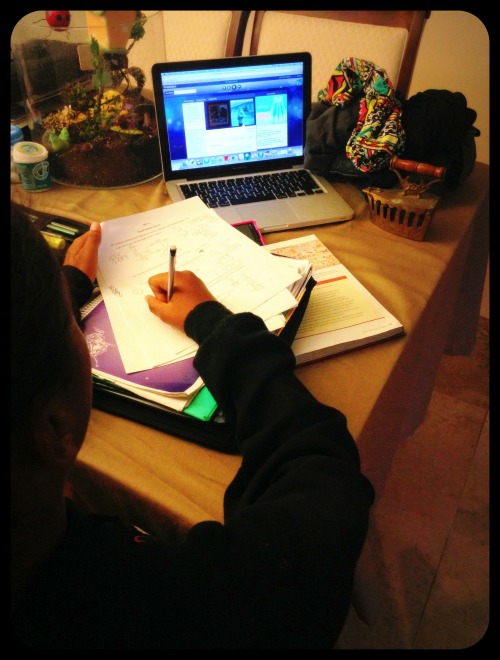

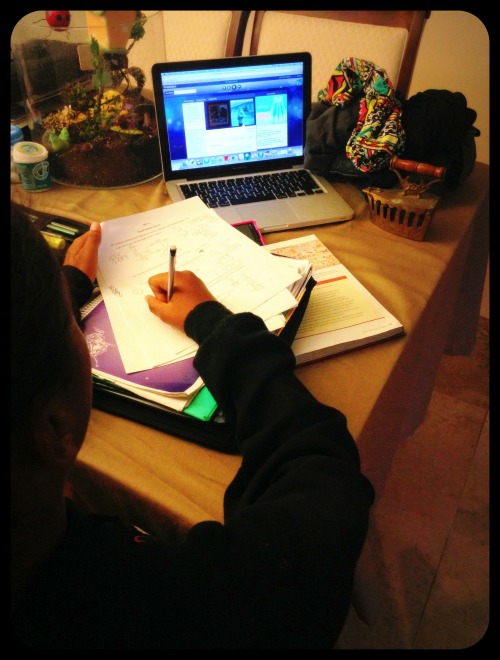

“But mom, why can’t I do my homework in front of the TV??? I’m not watching it, I’m just listening to it!!”, says my 12-year-old girl, emphasizing the word ‘watching’ with a half roll of the eyes.

My daughter is a really cool human & a great child. She is a tween so craziness and challenges come with the territory. Still, she has sweet moments, and she “OKs” everything, whether she remembers later or not.

But, my life was very different growing up in Italy and then Tanzania…

By age 9 my older brother & I alternated daily chores. We had to do dishes & sweep daily. There was no dillydallying, no talk-back, no having to dry our hands to like a song on Pandora…. none of that. We did homework on the kitchen table, our beds, in the yard, and wherever else. After I was done with homework I’d have to use the house phone, speak to a parent with good phone manners, & find out if my friends could come play. There was no texting them.

Everyone knew our plans; at least initially (smile). Outside we used our imagination to play with nothing. We picnicked under a tree in this huge sunflower field. We rode our bikes in circles in the bus’ parking lot and made sure we were home when the lights came on.

When I was 11 we moved back to Tanzania. Life here was drastically different, yet, in some respects there was more access to things than we had in the small Italian town we lived in. However, constant electricity and running water were gone. We had a western toilet in our home, but often had to use toilets requiring squatting, be they a hole over a sceptic tank, or an Eastern latrine. Not having water & electricity all the time required planning.

Though there was hired help, we also had to fetch water. If you don’t like fetching water you learn to use it sparingly. You take a shower from a bucket that’s a quarter full and come out clean! You recycle water so that first you wash your hair by dipping it into the bucket, then use the same water as the first cycle of your laundry, which you wash by hand. Having city-wide rationed electricity, meant ensuring you have kerosene, wick for lamps, and match sticks. You actually needed plenty of match sticks in Tanzania, because there is this one brand that makes them and you’re lucky if one out of five matches actually lights up & stays lit. HAHA!

We must see these things as humorous. Lack of electricity and paying for it in advance, meant using it responsibly. The radio would be on, and so would the TV for some parts of the day. We knew to close the fridge fast and to unplug the iron as soon as the job was done. Ironing was not always done with an electrical iron, either. Some times we would use a charcoal iron. It sounds like it’s from an entire different era, right? It’s still being used. A charcoal cast iron had to be used carefully. You’d also plan how to get hot coals so instead of wasting charcoal, kerosene fuel, and good match sticks, you’d use the charcoal for cooking. That required planning as well. A lot of planning and patience for a youngster, and children had to consider all these things from toddlerhood!

I am so infinitely grateful we lived this kind of life in my teenage years. Though I am sure I threw crazy hormonal arrows (figuratively speaking) at my mom, I think that having to deal with these realities made me get myself together quickly, thus sparing her six years of teenage craze. As far as school goes…wow! We had mandatory knee-high socks & buffed black shoes, mandatory hair pleats that I never had, monitors & prefects who thrived on their power to make us kneel for ‘misbehavior’, and hit-happy, switch-carrying teachers in the hallways who would whack you for no good reason.

In elementary school we had to chant….slowly & loudly…..”GOOD MORNING TEACHER!” Then we’d answer & ask, “FINE THANK YOU TEACHER, AND HOW ARE YOU, TEACHER?”, then we’d be permitted to sit down. In boarding school we had exactly 30 minutes to eat. The first year we ate food we individually cooked the night before, hoping it was still good without refrigeration. As a senior, food was made for us, so we’d hope it was ready & that we didn’t have to scoop bugs out of our beans. We’d always wash our dishes before returning to class. All of this, in 30 minutes.

At this school there was no corporal punishment. However, if we were late or didn’t follow other rules, we’d have some agricultural work for at least one period.

We studied in the hall after we cleaned our dinner mess. After two hours of supervised solid studying, we’d return to our hostel rooms (mine had four bunk beds with three beds each), and lights were out by 10pm. Everyone took showers in the morning, which I found to be unnecessary as the water was very cold, so I would leave some water in the courtyard for the sun to heat , and take a shower after school.

When I came to the United States I didn’t think I had a different work ethic than anyone else. I thought we all work hard & have different struggles. As the years passed I began to see certain differences & felt extremely fortunate for my history as it was.

As a girl I was lucky that my mother (who is partially Afghani & Punjabi) didn’t believe that I was worthless, blessed that she believed in education and sent me to school. I was also fortunate that I wasn’t betrothed at a young age, or at all. As I was in college I understood that I was privileged and had to make other women proud.

I would have to get the best grades, be a well-rounded student & not take electricity and running water for granted. So when my daughter asks why she can’t do her homework in front of TV, I don’t know what to say! OK, I do answer her, trying to use logic she’ll understand. She visited Tanzania for a few months in 2010, but she cannot relate to my history.

When my daughter was round age four she always asked if she could help with chores, but as I tried to rush I’d ask her to draw or play instead. I thought the environment around us would do for her what it did for me at her age. I knew I wasn’t in Italy, or in Tanzania, but I still thought I wouldn’t be the only one pushing for a balanced human. I also didn’t anticipate technology advancing so incredibly fast & how much gadgetry she would have at her disposal. In retrospect I should have encouraged her willingness to help.

She is now 12, doesn’t like to do any chores other than the occasional Swiffer mopping. She wants to do homework while listening to TV, somehow ignoring the visuals, and she wants to spend her other homework time listening to pop songs. She does practice Brazilian Jiu Jitsu and has a unique passion for it. But when not doing her school work, she looks at photos with funny quotes, watches short videos, and messages her friends on her phone. Our lives are so different. How do I teach her what I’ve been taught?

Is it drive? Is it thirst? Can you relate? How do you teach your children how to work hard? Please share your findings with me!

This is an original post to World Moms Blog by Sophia in Florida, USA. You can find her blogging at Think Say Be and on twitter @ThinkSayBeSNJ.

Photo credit to Trocaire. This photo has a creative commons attribution license.

I am a mom amongst some other titles life has fortunately given me. I love photography & the reward of someone being really happy about a photo I took of her/him. I work, I study, I try to pay attention to life. I like writing. I don't understand many things...especially why humans treat each other & other living & inanimate things so vilely sometimes. I like to be an idealist, but when most fails, I do my best to not be a pessimist: Life itself is entirely too beautiful, amazing & inspiring to forget that it is!

More Posts

Follow Me:

“Are you okay?” The emails and Facebook queries began pouring in even before I knew what had happened. “Were you there?” One particularly dramatic friend asked if “what happened” made me think about moving home.

“Are you okay?” The emails and Facebook queries began pouring in even before I knew what had happened. “Were you there?” One particularly dramatic friend asked if “what happened” made me think about moving home.

As a wife of one and a mom of four, it seems like I am always learning and discovering! I know I am not alone. Let’s just admit it: The world is a big place, life is a lesson, and children can be the best teachers. Normally my series, Life Lessons with Mexico Mom, is hosted on Los Gringos Locos, but today I am posting here on World Moms Blog.

As a wife of one and a mom of four, it seems like I am always learning and discovering! I know I am not alone. Let’s just admit it: The world is a big place, life is a lesson, and children can be the best teachers. Normally my series, Life Lessons with Mexico Mom, is hosted on Los Gringos Locos, but today I am posting here on World Moms Blog.