by Melanie Oda (Japan) | Apr 17, 2015 | 2015, Awareness, Cooking, Cultural Differences, Culture, Domesticity, Expat Life, Eye on Culture, Family, Food, Health, Home, Identity, International, Japan, Life, Life Balance, Living Abroad, Maternal Health, Me-Time, Motherhood, Multicultural, SAHM, Social Equality, Stress, Time, Traditions, Womanhood, World Motherhood

I start my morning here in Japan the same way every day: by cleaning out the drain trap.

I start my morning here in Japan the same way every day: by cleaning out the drain trap.

Not very pretty, I suppose, but I’ve learned the hard way that it needs to be done frequently and well. The drain traps here in Japan are metal mesh to prevent food from going down the drain. They get gross very quickly.

I’m pretty sure I started out my days when I lived in the US with a cup of coffee, which seems quite glamorous by comparison!

In spite of our gains in education or employment opportunities over the last century, much of our time as women gets taken up by mundane household tasks like this. Women all around the world are doing the same kind of things: laundry, food preparation, cleaning, child care, though in very different ways.

It makes me curious. How much of your time gets spent on “daily chores?” What kinds of things do you need to do every day? Do you do them alone, or do you have help?

Perhaps it is a boring topic, but for comparison I thought I would share a little bit of what housework is like here in Japan.

Laundry gets done daily in most families. We have washing machines, but most people don’t have dryers. In a country with cold winters, humid summers, and a rainy season, keeping up with the laundry feels like a daily battle! When the weather is not cooperative, laundry gets hung from curtain rails or any other overhang that can be found indoors. We have to bob and weave our way around the house. Imagine that Catherine Zeta Jones movie, but with laundry instead of lasers.

I do the shopping most days as well. This is quite common here in the greater Tokyo area, where storage space is limited and many people do not have cars to allow buying in bulk. Milk is sold by the liter; laundry detergent in 500ml bottles. The biggest shopping challenge is buying rice, which comes in 5 or 10kg bags.

I need to dust and vacuum every day. This is much more often than we did in the US growing up. I’m not sure why Japan is so dusty. Could it be the tatami floors? The single pane windows? The small living space? And more important than why, how can I make this dust accumulation stop?

Japanese cuisine seems to be gaining in popularity around the world. Many Japanese people eat a full meal in the morning (though this is slowly changing,) as well as at lunch and dinner. Japanese bento are also getting a lot of attention on the Internet for being nutritious as well as visually appealing. Overwhelmingly, the cooking is done by women. (Personally, since my children’s lunch is provided by the school, most days I cook twice.)

Like most families here, we have a gas stove-top, a rice cooker, and a microwave combined with an electric oven for cooking. My mother-in-law has a separate gas burner that can be placed on the table for doing things like sukiyaki or okonomiyaki, foods that are consumed as soon as they are cooked by the family from the same dish. My children are still a bit too small for me to attempt this at home.

I think many of us around the world are doing these same things, but the nitty-gritty of how we get it done and how often we do it are different. I can’t help but wonder what housework says about the values of the culture.

In the US, for example, many families take pride in a well-decorated home. In Japan that is much less important. (Perhaps because many women are spending all that time dusting and dodging laundry….)

What kinds of things are included in your daily duties? How do you feel about doing them?

This is an original post to World Moms Blog from our writer in Japan and mother of two, Melanie Oda.

The image used in this post is attributed to the author.

If you ask Melanie Oda where she is from, she will answer "Georgia." (Unless you ask her in Japanese. Then she will say "America.") It sounds nice, and it's a one-word answer, which is what most people expect. The truth is more complex. She moved around several small towns in the south growing up. Such is life when your father is a Southern Baptist preacher of the hellfire and brimstone variety.

She came to Japan in 2000 as an assistant language teacher, and has never managed to leave. She currently resides in Yokohama, on the outskirts of Tokyo (but please don't tell anyone she described it that way! Citizens of Yokohama have a lot of pride). No one is more surprised to find her here, married to a Japanese man and with two bilingual children (aged four and seven), than herself. And possibly her mother.

You can read more about her misadventures in Asia on her blog, HamakkoMommy.

More Posts

by Melanie Oda (Japan) | Jan 8, 2015 | 2014, Awareness, Child Care, Childhood, Culture, Domesticity, Education, Expat Life, Eye on Culture, Family, Feminism, Grandparent, Home, Husband, International, Japan, Life, Life Lesson, Living Abroad, Marriage, Me-Time, Motherhood, Multicultural, Parent Care, Parenting, Priorities, Relationships, Responsibility, School, Social Equality, Womanhood, Women's Rights, World Motherhood, Younger Children

Gender equality has been in the news quite a bit in Japan recently, sort of, and some things have happened closer to home that have me thinking.

Gender equality has been in the news quite a bit in Japan recently, sort of, and some things have happened closer to home that have me thinking.

It started when a (female) Tokyo assembly member was heckled in a sexist way. Then Prime Minister Abe introduced some new policies to let women “shine.” (He needs to get them doing something for the economy.) He even appointed several women to cabinet posts, for about five minutes, until they were slapped back down into their places over minor scandals.

In Japan, people are talking more about issues women face but no one seems to be doing much about them.

(Lest I forget: strangely enough, the declining birth rate is treated as a “women’s issue.” I seem to remember my husband being involved, too.)

I never considered myself a feminist growing up. Some members of the evangelical, conservative community I grew up in doubtless felt “feminist” was a new version of the “F-word.”

OK, so I went to a high school with more sports options for boys than girls. And yes, girls were encouraged to take chorus and home economics instead of woodworking or mechanics. So maybe I heard men from my community refer to grown women as “broads” or “gals.” There also were some restrictions at church regarding women’s and men’s roles. But I never felt that possessing certain types of baby-making parts limited my potential.

Then I moved to Japan, where gender roles are more firmly entrenched and my way of thinking slowly changed.

As I get older, and because I am a mother, I find that I am limited in ways that I couldn’t have foreseen as a young girl.

Some people may find life here in Japan freeing. If you aspire to be a homemaker a la Martha Stewart, then your life’s work would be very much respected and appreciated here. My husband wouldn’t bat an eyelid if he came home to a messy house because I’d spent the day at a preschool mothers’ lunch. He knows that is part of the job (on the other hand, it would never occur to him to pick up the mess himself.)

If, as a woman, you have other aspirations, Japanese culture seems designed to work against you. The glass ceiling is very much in tact. On the news here you do hear issues like lack of childcare and “maternity harassment” being addressed. But what gets talked about less often is that to many women, including myself, it feels as if there’s a glass door as well.

It’s my front door.

Before a woman can even think about what is facing her out in the world, she needs to address the forces that are keeping her at home. Some of these are practical, some are logistical, some are cultural and perhaps peculiar to Japan and it’s work culture.

For me, it starts with my husband: He leaves home at 7am every morning, but I have no idea what time he will be back. Sometimes it’s 7pm. Sometimes it’s midnight. He may be in the office that day, or he may suddenly be sent to another prefecture. He’s made international trips on 12 hours notice. I cannot depend on him being home at a designated time, by no fault of his own. The idea of him taking time off with a sick child is preposterous in the extreme.

I have been lucky enough to have two job offers recently, both of which would be more or less during school hours, but neither is nearby. If a child were to get sick and need picking up, or if god-forbid there was a natural disaster (which is always in the back of your mind if you are a mother in Japan,) then my husband would be closer. I mentioned that, and he completely shot me down. Not just the idea of him picking up the kids in case of an emergency, but the idea of a job anywhere outside of cycling distance from the school.

We live in a residential neighborhood. I patch together some part-time work here and there, but it’s not like there are loads of professional opportunities in a two kilometer radius.

I suddenly felt very limited, penned in, in a way I haven’t felt before. The glass door was slamming in my face.

I don’t think I’m alone in this conundrum. Go to almost any supermarket in a residential area during the day, and you will see women in their prime working years manning the register. Many of these women have university degrees. Many have licenses and qualifications to be doing other kinds of work, but they want to stay close to home. They also need salaries to stay under $10,000 year or face a peculiar Japanese tax code and insurance system that penalizes families where both partners have incomes over that amount.

Then there are my kids: Like 2/3 of Japanese women with children under 6, I stayed home when they were small. They now completely depend on me for everything. It seems to have never entered their minds that someone else could give them a bath or help them find their missing socks, mostly because no one else has ever done anything for them. Especially when they are sick, they want only me. It was very hard when my daughter was in the hospital, both children wanting to be with me and emphatic that no one else would do.

But now my youngest is in elementary school, and I would like to just be doing more of something….else, but for me to plunge into the workforce would be a huge adjustment for my children. Is it worth the stress? Can we survive what is sure to be a painful adjustment period?

Maybe if I had more family support, it would feel less impossible but as it is, it seems like everyone is against me.

Which brings me to the final characters in this comedy, my in-laws: They say they’ll watch the kids, then they change their minds. Or something better comes up. From their point of view, this house and these people are completely my responsibility. Anything they do is extra credit.

To be honest, we’re getting to the point where my in-laws need my help more than I need theirs.

They aren’t shy about letting me know my place.

One day not too long ago, my son was playing at the park with his friends. It was getting close to homework time, so I called him and told him to come home. He said he was playing with Jiji (which is an endearing term for grandfather used in our region of Japan,) and could he play for a bit longer? Since he was out with an adult, I said okay.

The next day, I got a verbal whipping from my father-in-law over the phone, accusing me of being irresponsible, a bad mother. It took me a few minutes to understand why he was saying this, but when I got to the bottom of it, I realized my son had lied to me. He was playing with his friends when Jiji walked by and told him to go home. My son told him I wasn’t at home and said he couldn’t come back until I did. (I must have called right at this point.) “How dare you not be home in the afternoon?” said Jiji.

Putting aside that none of this nonsense was true, so what if I wasn’t home in the afternoon? Of course I wouldn’t have left the kids to wander the neighborhood like stray dogs, but why was my not physically being inside my house such an issue to him? His assumption that it was my duty to be always available to everyone took me by surprise.

I could almost hear the glass door slamming again.

There are also other barriers for women in Japan—an over active PTA for one, and a myriad of community responsibilities attended to exclusively by women for another. I imagine most women in the world encounter both the “glass door” and the “glass ceiling” in some form or another, but in Japan only one of these factors is seems to be getting much attention. Building new daycare facilities isn’t enough; the government stating goals to increase women’s participation in the workforce isn’t enough. Until we do something about that glass door, nothing will change for one of the best educated, least utilized group of women in the world.

Do you feel you are fulfilling your potential, both at work and at home? What’s the situation like in your country?

This is an original post for World Moms Blog from our writer and mother of two in Japan, Melanie Oda.

If you ask Melanie Oda where she is from, she will answer "Georgia." (Unless you ask her in Japanese. Then she will say "America.") It sounds nice, and it's a one-word answer, which is what most people expect. The truth is more complex. She moved around several small towns in the south growing up. Such is life when your father is a Southern Baptist preacher of the hellfire and brimstone variety.

She came to Japan in 2000 as an assistant language teacher, and has never managed to leave. She currently resides in Yokohama, on the outskirts of Tokyo (but please don't tell anyone she described it that way! Citizens of Yokohama have a lot of pride). No one is more surprised to find her here, married to a Japanese man and with two bilingual children (aged four and seven), than herself. And possibly her mother.

You can read more about her misadventures in Asia on her blog, HamakkoMommy.

More Posts

by Melanie Oda (Japan) | Oct 16, 2014 | 2014, Awareness, Being Thankful, Child Care, Childhood, Cultural Differences, Culture, Expat Life, Eye on Culture, Family, Health, Hospital, International, Japan, Kids, Life Balance, Life Lesson, Living Abroad, Milestones, Motherhood, Parenting, World Motherhood, Younger Children

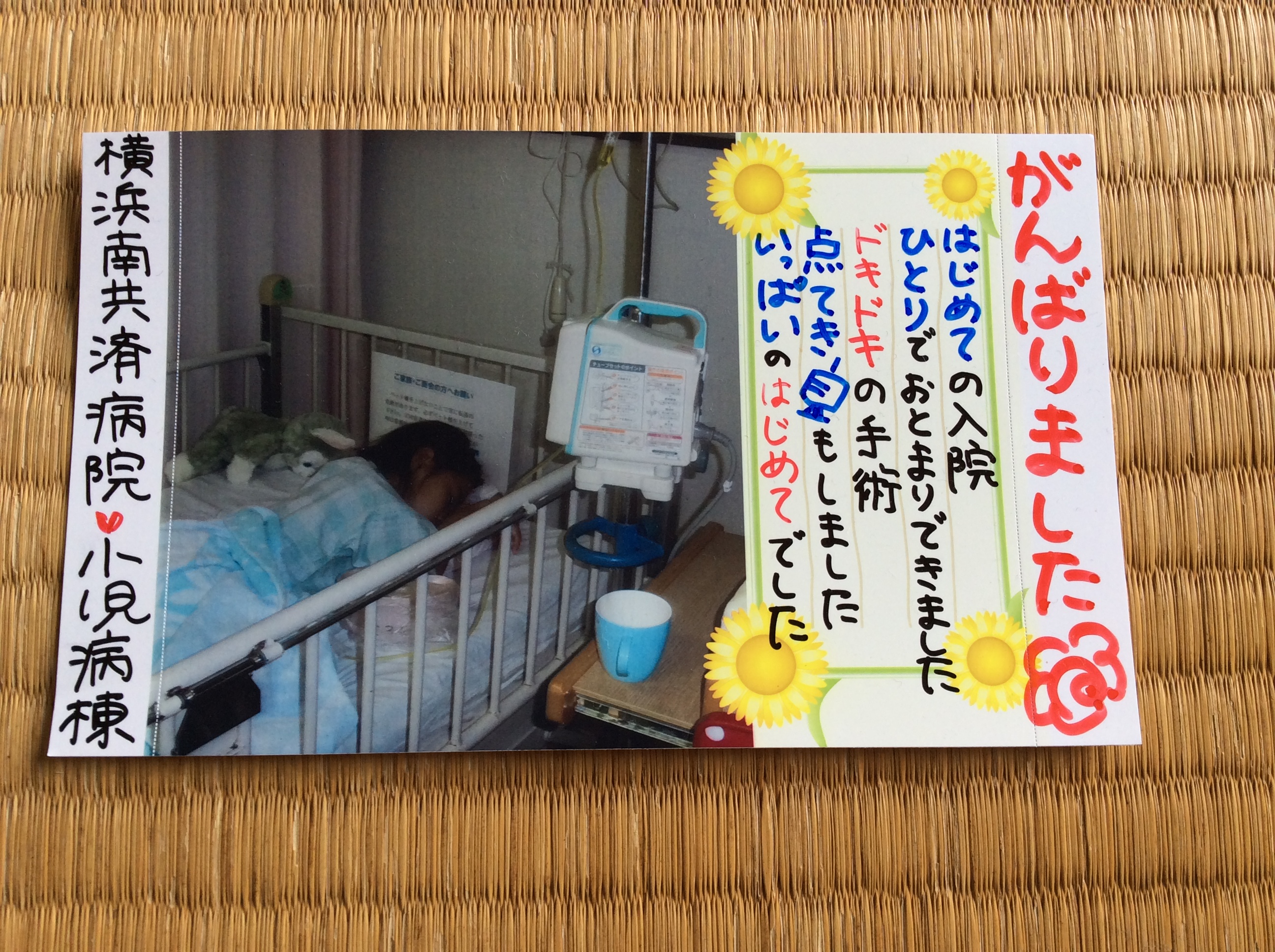

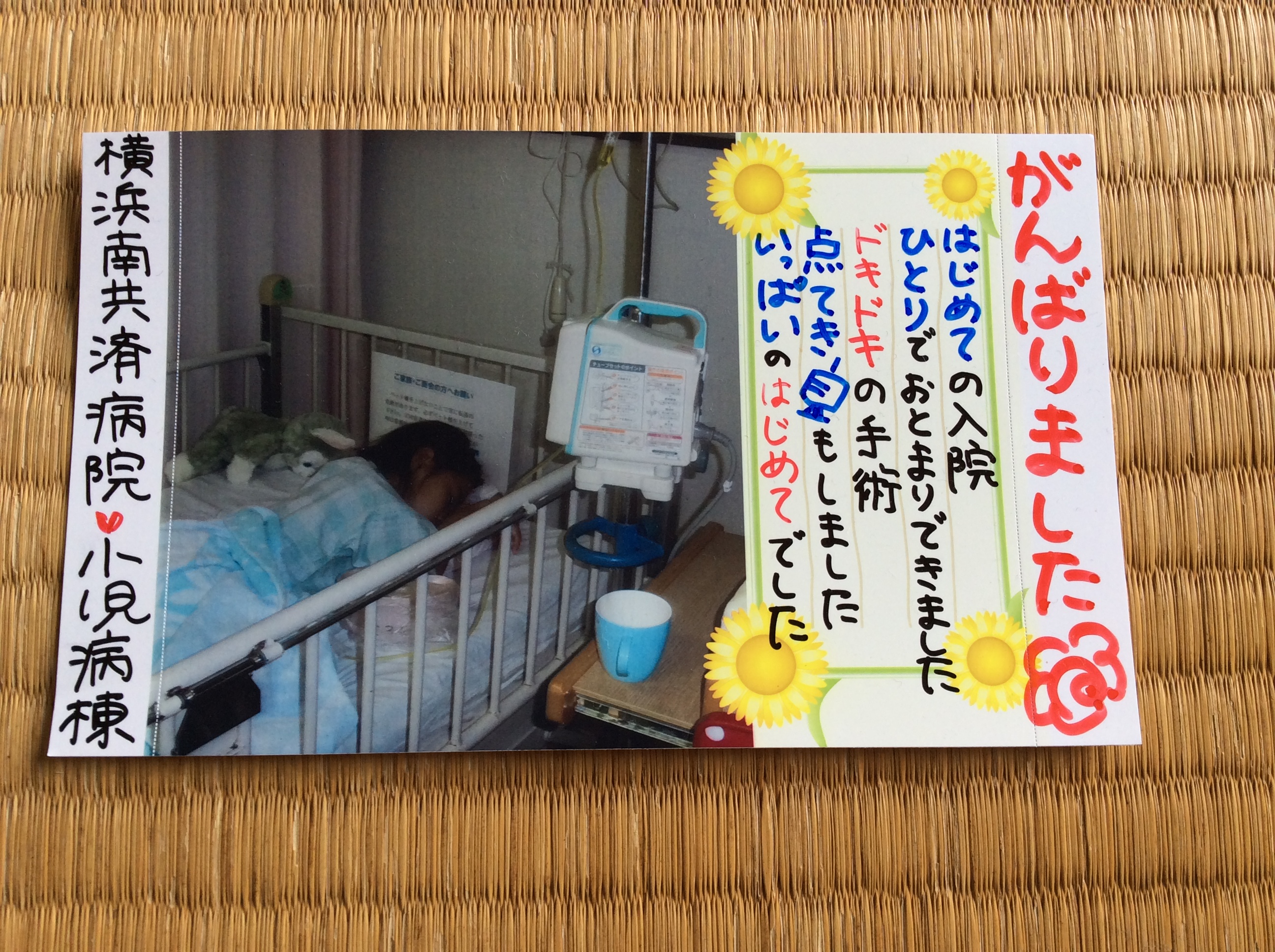

My 6 year-old daughter had her tonsils and adenoids out over summer vacation. She had been diagnosed with sleep apnea several months earlier and since nothing else was helping, finally I reluctantly agreed to the surgery.

My 6 year-old daughter had her tonsils and adenoids out over summer vacation. She had been diagnosed with sleep apnea several months earlier and since nothing else was helping, finally I reluctantly agreed to the surgery.

I was reluctant because hospital “culture” in Japan is very different from the US, where I am from, and because I knew I would be up against another cultural wall in regards to care for my older child.

This surgery, that requires a one-night stay in the hospital in either the US or UK (according to some quick research on my part,) here in Japan means seven nights in the hospital.

Since hospital rooms are shared, parents are not allowed to stay over night for any except the youngest of patients. Parents are expected to provide clean laundry and cutlery for the patient every day.

The children’s ward had a strict daily schedule, with times when they we’re confined to their beds (which literally had bars like a prison cell,) and times when, if they were well enough, they were allowed to use the playroom.

But absolutely under no circumstances whatever could they leave the children’s ward. And visitors under the age of 15 were not allowed in the ward.

This was a conundrum for me. I have a 9 year old son, who was on summer vacation at the time, and a husband who works 12 hour days, on a good day.

Hospital culture in Japan is strangely at odds with the wider culture in general. A high percentage of children co-sleep with their parents well into their elementary years. That is the cultural norm.

However, the hospital where my daughter had surgery, would not allow parents to spend the night with children over 2 years old.

This particular hospital allows parents of small children to stay until they fall asleep, but for my daughter, that may actually have been worse. Come lights out at 8pm, there was more crying in the children’s ward than from the nursery down the hall.

I had another child waiting at his friend’s house or at Baba’s (grandmother’s) house for me to come home, after all. My husband tried to get home from work at a decent hour, but I think he made it by 7pm once.

The day after the surgery, when my daughter was still feeling ill from the effects of the anesthesia and started bleeding from her nose, I was very grateful that she was in the hospital where I could have a professional attend to any concerns with the push of a nurse-call button.

Around Day 3, though, I could feel myself beginning to fall apart, fiber by fiber. The stress and plain old-fashioned exhaustion were starting to get to me.

My son at home was starting to feel the effects of being shuffled from place to place numerous times a day. My daughter wasn’t sleeping well and wanted to come home. I begged the doctor to discharge her a bit early, even a few hours would be great. His response was that the other child in the same room who’d had the same surgery on the same day was not recovering as well, and it would be upsetting for her if mine left earlier.

Excuse me, what? I thought, blinking several times, sure I had misheard. But I hadn’t.

On the day she was finally discharged, the nurses and staff presented her with a postcard, complete with a photo of her post-op, “to remember them by.” My first instinct was to burn it. Who would want to remember this? But I kept it, an ironic little reminder of the Japanese tendency to have “entrance” and “exit” ceremonies for everything.

I was reminded of a speech the principal of a junior high gave to the student body to announce that I was leaving: “People enter our lives, and at some point we must be parted. We should cherish each of these events.” Perhaps one day my daughter will value the card.

For now, she gets angry every time she sees it. The poor little girl has been waking up at night just “making sure I’m at home” for the past several weeks.

But now I look at the card and I feel profoundly thankful that my kids are, for the most part, healthy and happy. I don’t know how parents, who have to juggle (and it is a juggling with knives-type event, not harmless bean bags) a child’s hospitalization—along with the mundane tasks of everyday life that just keep coming, even when we are least able to deal with them—do it.

I say a little prayer for you every night, moms I do not know, and wish you strength and patience and space to breathe.

Has your child ever been hospitalized? What was it like for you, as a parent?

This is an original post to World Moms Blog from our mother of two in Japan, Melanie Oda.

The image used in this post is credited to the author.

If you ask Melanie Oda where she is from, she will answer "Georgia." (Unless you ask her in Japanese. Then she will say "America.") It sounds nice, and it's a one-word answer, which is what most people expect. The truth is more complex. She moved around several small towns in the south growing up. Such is life when your father is a Southern Baptist preacher of the hellfire and brimstone variety.

She came to Japan in 2000 as an assistant language teacher, and has never managed to leave. She currently resides in Yokohama, on the outskirts of Tokyo (but please don't tell anyone she described it that way! Citizens of Yokohama have a lot of pride). No one is more surprised to find her here, married to a Japanese man and with two bilingual children (aged four and seven), than herself. And possibly her mother.

You can read more about her misadventures in Asia on her blog, HamakkoMommy.

More Posts

by Melanie Oda (Japan) | Jul 31, 2014 | 2014, Cultural Differences, Food, Japan, School, World Moms Blog

chow_time

I read on the internet a lot about how America is trying to change their school lunch program and make it healthier. And I read a lot about how some people are not happy about this. They complain that kids won’t eat what they don’t like, food gets wasted, etc.

All of that may be true. But I thought I would share what school lunch is like here in Japan.

Children in elementary schools across the country receive a hot lunch every day. The menu is widely varied, with international kid favorites like spaghetti with tomato sauce, the local preference of curry and rice with salad and yogurt, to more traditional foods like fish with miso sauce, vegetable pickles, and wakame seaweed soup. Most days the meals are heavy on vegetables. They include fruit in season occasionally, and maybe once a month or so there is a light desert like jelly (jell-o) or ice cream. Some days they have rice, other days they have bread, still other they have noodles.

And, with a few exceptions, the kids love it!

Why is that?

Part of the reason may be attitude. When my husband was a kid, they didn’t have the facilities to prepare rice and noodles, so he looks at the monthly menu and says “ii na-,” I wish I could have had that! Let’s go back another generation, to my father-in-law. He had bread and milk only every day (ironically enough, he says it was supplied by the occupying US forces,) and he was grateful for it at a time when there may or may not have been dinner waiting for him at home. But- hamburger steak and pickled cabbage with tomatoes? “Ii na!”

In our city, preschoolers, junior high kids, and high school kids have to take their lunch. A bento lunch can be a wonderful thing, but it isn’t hot and doesn’t come with milk.

But perhaps the most important reason is that the kids themselves are involved in food preparation. Each week, half the class is in charge of serving the other half. They carry the pots and trays and multiple little dishes and utensils up to their classrooms, then ladle and scoop and pass the food to each other. When time is up, they clean it up and go have recess.

So if you don’t eat, or you take too long, you make your friends late for recess. That’s quite a motivator there, isn’t it?

Japanese children, in most cases, don’t have the option of taking their lunch if what’s on the menu that day isn’t to their liking. When my son was in first grade, that really bothered me. There were days when he only ate rice, or only ate bread, and I would have been happy to have been able to pack him a sandwich or a banana or something! But after being faced with foods he wouldn’t normally try, day after day, he’s blossomed into quite the adventurous eater. He eats so many different things now. Dinner time is much less of a battle than it used to be, and I think that’s due to the varied and interesting food he gets at school every day.

Do your children have a hot lunch at school? What’s on the menu for chow time?

This is an original post by World Moms Blog contributor, Melanie Oda in Japan, of Hamakko Mommy.

Photo credit to the author.

If you ask Melanie Oda where she is from, she will answer "Georgia." (Unless you ask her in Japanese. Then she will say "America.") It sounds nice, and it's a one-word answer, which is what most people expect. The truth is more complex. She moved around several small towns in the south growing up. Such is life when your father is a Southern Baptist preacher of the hellfire and brimstone variety.

She came to Japan in 2000 as an assistant language teacher, and has never managed to leave. She currently resides in Yokohama, on the outskirts of Tokyo (but please don't tell anyone she described it that way! Citizens of Yokohama have a lot of pride). No one is more surprised to find her here, married to a Japanese man and with two bilingual children (aged four and seven), than herself. And possibly her mother.

You can read more about her misadventures in Asia on her blog, HamakkoMommy.

More Posts

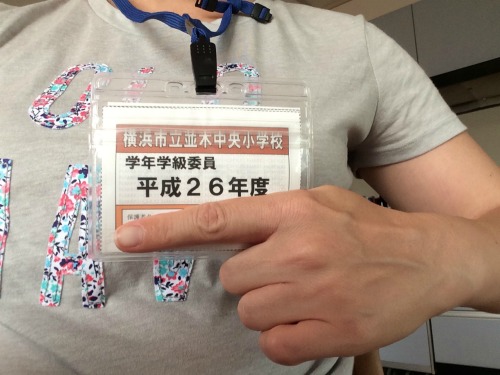

by Melanie Oda (Japan) | Jun 5, 2014 | 2014, Japan, Parent Care, School

I have vague memories of the Parent Teachers Association (PTA) in the US, where I grew up. I remember the occasional school-wide meeting being held in the evening and a fall festival here, or there, involving baked goods. I’m not sure how much of my non-memory is due to just being an average kid (that is, extremely self-involved and just not noticing what the grown-ups were doing) or if the whole thing was just lower key.

Or, perhaps, my parents had some choice in the matter.

At any rate, PTA membership in Japan is by default. They take the fees out of your bank account right along with school supplies and school lunch payments. (Lunches her are amazing, by the way. A topic for another post.) I don’t know if it’s possible to opt out, or not. I certainly don’t know anyone who has tried!

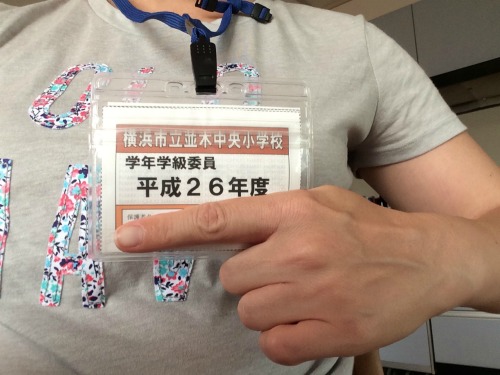

The PTA at my children’s school is arranged like a pyramid, and at the top are the officers. Beneath them are the leaders of the four councils: class representatives, safety, and … well, in Japanese they call it “public information”, the group that makes the quarterly newsletter, along with the nomination committee. (These are the guys that try to suck you into being an officer for the next school year). Underneath that are the representatives from each class, and beneath all that is everyone else.

You are expected to serve on one of these councils at least once for each child.

This year, I ended up being the class rep for the first grade.

- Our job is to organize a school lunch “tasting day,” when parents can have lunch at school. But not with their child, in the Home EC room. (Both my daughter and I were disappointed by that.)

- Arrange and execute the washing of all the schools curtains. Twice. (I didn’t realize I should be washing my curtains at home twice a year….oops.)

- Collect and prepare for posting “bell marks,” the Japanese version of “Boxtops for Education,” collecting proofs of purchases that can be exchanged for school supplies.

- And lastly, mending the white smocks that children wear when distributing school lunches (in Japan, the children help prepare the lunch.)

Whew, that was quite a list!

Of course, all of these jobs require multiple letters sent home, which we prepare, and monthly meetings because … well, because this is Japan, perhaps.

Every family without fail is to volunteer for one of the tasks, either washing curtains, helping organize the bell marks, or mending the smocks.

When my oldest child started school, I was really surprised that the PTA were in charge of things that were so nitty-gritty.

I’m pretty sure, for example, the my mother never washed school curtains in her washing machine and then hauled them back to school to hang them up, still wet, after cleaning the school’s curtains rails.

So it makes me wonder …

What is PTA like in your country? Do you have to participate? What kind of things do you do?

This is an original post by our World Mom Melanie Oda from Japan.

Photo credit to the author.

If you ask Melanie Oda where she is from, she will answer "Georgia." (Unless you ask her in Japanese. Then she will say "America.") It sounds nice, and it's a one-word answer, which is what most people expect. The truth is more complex. She moved around several small towns in the south growing up. Such is life when your father is a Southern Baptist preacher of the hellfire and brimstone variety.

She came to Japan in 2000 as an assistant language teacher, and has never managed to leave. She currently resides in Yokohama, on the outskirts of Tokyo (but please don't tell anyone she described it that way! Citizens of Yokohama have a lot of pride). No one is more surprised to find her here, married to a Japanese man and with two bilingual children (aged four and seven), than herself. And possibly her mother.

You can read more about her misadventures in Asia on her blog, HamakkoMommy.

More Posts

I start my morning here in Japan the same way every day: by cleaning out the drain trap.

I start my morning here in Japan the same way every day: by cleaning out the drain trap.